(from the AHNS Cutaneous Cancer Section)

by Yusuf Dundar, MD & A. Daniel Pinheiro, MD PhD

Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from a cutaneous primary (cSCC) is the most common histology in patients with parotid gland metastasis. The standard treatment for cSCC with direct parotid gland invasion or intra-parotid lymph node metastasis is surgical excision and, in some cases, adjuvant radiotherapy +/- chemotherapy depending on presence of high-risk features. The extent of surgical intervention is controversial when there is no evidence of cervical lymph node metastasis.1 Since there are no prospective randomized trials regarding management of the cN0 neck in patients with parotid gland metastases, we have to rely on observational data from retrospective reviews (although in some the data were collected prospectively).

One area of controversy is the management of the deep lobe when there are cSCC metastases to the superficial lobe. Obviously, the minimum standard would include superficial parotidectomy with facial nerve dissection (SP). Some have proposed dissection of the deep lobe sparing the facial nerve (i.e., total conservative parotidectomy -TCP – as opposed to total radical parotidectomy) when there is disease in the superficial lobe. The reasons for additional surgery to remove the deep lobe are the fact that studies have shown occult metastatic disease to the deep parotid lobe2. In one retrospective single-institution series which included 42 patients with cSCC metastatic to the parotid, 26% of patients had occult metastases to the deep parotid lobe3. In that study, parotid bed local control was reported to be 93% for patients with cSCC3 and arguably local control might have been lower if the occult disease in the deep lobe had not been removed. However, since most of these patients have indications for adjuvant radiation, it is difficult to demonstrate if there is an additional benefit of TCP as opposed to just removing the parotid tissue lateral to the facial nerve, i.e., SP. For instance, in another retrospective review, Hirshoren et al.4 reported that 65 of 78 patients with cSCC metastatic to the parotid had SP instead of total parotidectomy. The parotid bed local control in those who received adjuvant radiation was 96.3% and they argued that more extensive parotid surgery might not be needed. However, the local control for those who did not receive radiation dropped to 73%. Therefore, there may be a role for TCP when the disease in the superficial lobe is limited without any a priori indications for adjuvant radiation. Even so, some would argue against TCP because of added dissection time, increased risk of facial nerve injury (at least transiently) and additional aesthetic deformity from loss of volume in pre-auricular area.

Occult nodal disease in cervical lymph nodes is considered a high-risk feature and poor prognostic factor, which requires appropriate treatment. Weiss et al. introduced a decision tree analysis in planning for elective neck dissection (END) for clinically N0 necks and proposed a 20% cut off to offer END for head and neck squamous cell cancers.5 There are variable data regarding occult cervical nodal metastasis in patients with clinically positive parotid metastasis, ranging from 14.7% to 45.2%.6,7 A recently published meta-analysis reported 22.5% occult cervical metastasis.8 Ebrahimi et al reported Level II is the most commonly involved compartment (35.6%), followed by level III (14.6%).9 Patients without any Level II or III nodal involvement did not display disease in level IV or Level V. O’Brien et al. and Vauterin et al. reported similar results.1,10 Aggressive tumor histological features, advanced T stage, thick/deep primary tumors, immunosuppression, and pre-auricular primary tumor location were high risk features for having occult cervical node metastasis.

Cervical lymph node involvement is associated with poor survival outcomes. Five-year disease specific survival (DSS) and overall survival (OS) rates were reported ranging from 58% to 83% and from 48% to 80%, respectively in patients with cervical nodal metastasis. 8 However, there were no data available to compare survival rates in patients with occult metastasis relative to those with clinically positive nodes. There were very limited data on those treated by elective neck irradiation (ENI) versus END followed by adjuvant radiotherapy for patients with parotid metastasis. Herman et al compared recurrence rates following ENI versus END and adjuvant radiotherapy.11 The recurrence rates were reported as 1.5% and 2.4% in ENI and END + adjuvant radiotherapy arms respectively (p > 0.05). The recurrence rates were not statistically significant, and the study had many limitations including retrospective setting, high occult nodal metastasis in surgery arm (45.2%), and limited number of patients in study arms. The other limitation of elective neck irradiation is the inability to pathologically stage the neck. Additionally, there is a concern that the addition of neck dissection may increase complication rates, but literature is scant in this area.

The literature supports that there is a high incidence of occult cervical nodal invasion (22.5%) in patients with clinically positive parotid metastasis who meet the criteria to offer END per the Weiss principle. However, this decision tree analysis is designed for purely clinically N0 necks. The patient population with clinically positive parotid metastasis has already demonstrated metastatic potential. Thus, it seems very reasonable to offer END as an addition to the Weiss principle. The extent of neck dissection should include at least level II and III, and typically, supraomohyoid (Level I, II and III) neck dissection is recommended. However, the location of the primary tumor may further inform the surgical plan (eg; posterior scalp, midface tumors, or primary unknown tumors).

Recently, the addition of neoadjuvant immunotherapy is being considered for cases with advanced parotid metastases based upon small, early studies. It is unclear how the consideration of elective neck dissection would be affected in this population. At this point, the use of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in these patients should be reserved to the clinical trial setting.

References:

- O’Brien CJ, McNeil EB, McMahon JD, Pathak I, Lauer CS, Jackson MA. Significance of clinical stage, extent of surgery, and pathologic findings in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck. 2002;24(5):417-422.

- Pisani P, Ramponi A, Pia F. The deep parotid lymph nodes: an anatomical and oncological study. J Laryngol Otol. 1996 Feb;110(2):148-50. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100133006. PMID: 8729499.

- Thom JJ, Moore EJ, Price DL, Kasperbauer JL, Starkman SJ, Olsen KD. The Role of Total Parotidectomy for Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Malignant Melanoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Jun;140(6):548-54. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.352. PMID: 24722863.

- Hirshoren N, Ruskin O, McDowell LJ, Magarey M, Kleid S, Dixon BJ. Management of Parotid Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Regional Recurrence Rates and Survival. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Aug;159(2):293-299. doi: 10.1177/0194599818764348. Epub 2018 Mar 13. PMID: 29533706.

- Weiss MH, Harrison LB, Isaacs RS. Use of decision analysis in planning a management strategy for the stage N0 neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:699-702.

- Palme CE, O’Brien CJ, Veness MJ, McNeil EB, Bron LP, Morgan GJ. Extent of parotid disease influences outcome in patients with metastatic cuta-neous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003; 129(7):750-753.

- Herman MP, Amdur RJ, Werning JW, Dziegielewski P, Morris CG, Mendenhall WM. Elective neck management for squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the parotid area lymph nodes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3875-3879.

- Rotman A, Kerr SJ, Giddings CEB. Elective neck dissection in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma to the parotid gland: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2019 Apr;41(4):1131-1139.

- Ebrahimi A, Moncrieff MD, Clark JR, et al. Predicting the pattern of regional metastases from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck based on location of the primary. Head Neck. 2010;32:1288-1294.

- Vauterin TJ, Veness MJ, Morgan GJ, Poulsen MG, O’Brien CJ. Patterns of lymph node spread of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2006;28(9):785-791.

- Herman MP, Amdur RJ, Werning JW, Dziegielewski P, Morris CG, Mendenhall WM. Elective neck management for squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to the parotid area lymph nodes. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3875-3879.

Yusuf Dundar, MD – An Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology and Head&Neck Surgery at Texas Tech University (Lubbock/Texas). Dr. Dundar specializes in all aspects of head and neck oncology, including cutaneous malignancies, salivary gland cancers, thyroid cancers, mucosal head and neck cancers. He also performs complex microvascular reconstruction of the head and neck as well as transoral robotic surgery.

Yusuf Dundar, MD – An Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology and Head&Neck Surgery at Texas Tech University (Lubbock/Texas). Dr. Dundar specializes in all aspects of head and neck oncology, including cutaneous malignancies, salivary gland cancers, thyroid cancers, mucosal head and neck cancers. He also performs complex microvascular reconstruction of the head and neck as well as transoral robotic surgery.

Daniel Pinheiro, MD PhD FACS – Daniel PInheiro is a head and neck surgeon at Mercy Clinic in Springfield, MO. He is the Director of Surgical Oncology at Mercy Clinic and has an interest in outcomes research. His clinical areas of expertise are in oropharynx cancer and endocrine head and neck surgery.

Daniel Pinheiro, MD PhD FACS – Daniel PInheiro is a head and neck surgeon at Mercy Clinic in Springfield, MO. He is the Director of Surgical Oncology at Mercy Clinic and has an interest in outcomes research. His clinical areas of expertise are in oropharynx cancer and endocrine head and neck surgery.

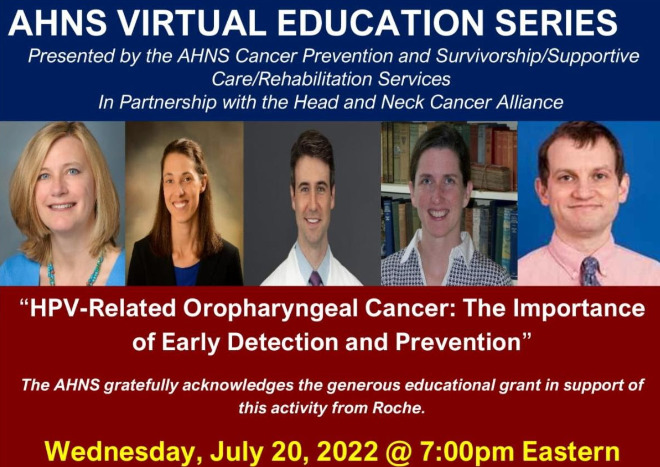

TODAY: AHNS Educational Series: Presented by AHNS In Partnership with the Head and Neck Alliance “HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: The Importance of Early Detection & Prevention

TODAY: AHNS Educational Series: Presented by AHNS In Partnership with the Head and Neck Alliance “HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: The Importance of Early Detection & Prevention