Authored by Charles Coffey, MD & Tamer Ghanem, MD PhD; edited by Ellie Maghami, MD FACS

AHNS Education Committee

Introduction

This document is intended to introduce a subtype of head and neck cancer known as oropharynx cancer, and the normal anatomy and physiology of the oropharynx will be reviewed. Factors that can lead to cancer formation in this area are defined. Information regarding diagnosis, treatment, and expected outcomes of this condition is provided.

Anatomy & Functional Considerations

The oropharynx is the middle compartment of the pharynx, i.e. throat; it is the region of the throat between the nasopharynx (top compartment) and hypopharynx (bottom compartment). The oropharynx includes the tonsils, tongue base, soft palate, and pharyngeal walls. Several of these subsites are very common locations for the development of head and neck cancer, and a tumor present in any of these subsites can be broadly categorized as an oropharyngeal tumor. It is important to distinguish the oropharynx from the oral cavity (mouth), as tumors arising in these two sites may behave differently and require very different considerations regarding function and appropriate treatment.

The tonsils (also referred to as palatine tonsils) are collections of lymphoid tissue located on each side of the oropharynx which participate in the immune function of the aerodigestive tract. Although tonsils may be quite large during childhood, they generally regress with age, and many adults have very little visible tonsillar tissue remaining. Enlargement or asymmetry of the tonsils in an adult may simply be an anatomic variant, but may also be an indication of tumor presence. Removal of tonsils has not been found to compromise immune status.

The base of tongue (or tongue base) refers to the portion of the tongue which resides in the oropharynx (posterior 1/3 of the tongue). The base of tongue is functionally and anatomically distinct from the oral tongue, which is the portion of the tongue which resides in the oral cavity (anterior 2/3 of the tongue) and is most important for speech and language. The muscles of the base of tongue are more involved with swallowing than speech, and play a critical role in controlling the passage of food and liquids from the mouth into the throat. Base of tongue dysfunction resulting from tumor, loss of tissue due to surgery, or radiation-related effects may result in difficulty swallowing or aspiration (spillage of liquids into the larynx or voicebox).

The soft palate is a muscular soft tissue sling which resides behind the hard palate, or roof of the mouth. The soft palate separates the nose and nasopharynx from the remainder of the pharynx and oral cavity during speech and swallowing. Inability to close the soft palate (velopharyngeal insufficiency) due to tumor, resection, or scar may result in hypernasal speech as well as reflux of liquids into the nose during swallowing. The lateral and posterior walls of the oropharynx are comprised primarily of muscles which play a supporting role in the pharyngeal phase of swallowing.

Epidemiology

The oropharynx is one of the most common sites of head and neck cancer in the United States. It is estimated that 11,000-13,000 new cases of oropharyngeal cancer are diagnosed in the United States each year (Jemal; Siegel; CDC). The vast majority of these tumors are squamous cell carcinoma, a cancer which arises from squamous epithelial cells which line the upper aerodigestive tract. Squamous cell carcinomas may also arise at numerous other sites including the skin, lungs, bladder, and cervix, but tumor behavior and treatment options vary greatly across different body sites. Males are more than four times as likely as females to develop oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), with an overall annual risk of 6.2 per 100,000 men compared to 1.4 cases per 100,000 women (Jemal, CDC). Incidence in the U.S. is highest among white and black men, and lower among Hispanics, Native Americans and Asians/ Pacific Islanders.

Risk Factors

Tobacco and Alcohol

Tobacco use has been strongly established as the primary risk factor in the majority of head and neck aerodigestive tract cancers (Sturgis 04, Sturgis 07). Lifetime risk of developing head and neck cancer is increased 10-fold in smokers, and the magnitude of risk increases up to 25-fold for the heaviest smokers. Alcohol use is an independent risk factor for development of head and neck cancer. Although the risk is higher with chronic heavy alcohol use, there is some evidence that light alcohol use may also increase risk of developing oropharyngeal cancer (Bagnardi). Combined use of both tobacco and alcohol further increase cancer risk (Masberg). Historically, up to 90% of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma including OPSCC has been attributed to tobacco use and alcohol abuse (Sturgis 04). Tobacco use in the United States has been steadily declining for the last five decades, with the percentage of active smokers decreasing from 43% in 1965 to below 20% in 2010 (Mariolis, Skinner). Per capita alcohol use has shown a more modest decline, from 2.7 gallons per year in the mid-1980s to 2.26 gallons per year in 2010 (LaVallee). These trends have generally been paralleled by decreasing rates of head and neck cancer incidence and mortality.

Human Papilloma Virus

Despite decreasing rates of tobacco and alcohol use, the rates of oropharyngeal cancer have trended steadily upward for the last decade. This is primarily due to the increase in cancers related to infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV). Human papilloma viruses are a large group of related viruses which are spread through vaginal, oral and anal sex. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, affecting more than half of sexually active individuals at some point during their lives (NCI). Several strains of HPV are associated with increased risk of developing cervical, genital, and oropharyngeal cancers. Infection of epithelial cells by high-risk strains of HPV is associated with production of viral proteins which may eventually interfere with the cell’s normal ability to suppress tumor growth. The immune system successfully eliminates HPV infection in most patients, and only a small portion of patients infected with high-risk HPV strains will develop an HPV-related cancer. It is estimated that approximately 7% of those aged 14 to 69 years in the U.S. have oral HPV infection at any one time, as detected by an oral rinse. Approximately half (3.7%) of those infections are with high-risk HPV strains (Gillison 2012; Sanders). The time lag between an oral HPV infection and the development of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is estimated at between 15 and 30 years. As such, the rise in OPSCC seen since the 1990s in large part reflects changes in sexual practices in the 1960s and 1970s.

The risk profile for HPV-related OPSCC differs from most head and neck cancers. When compared to patients with non-HPV tumors, patients with HPV-positive OPSCC are more likely to be young, white, higher socioeconomic status, non-smokers, and non-drinkers. Sexual history is strongly associated with HPV-positive cancers. Significant increase in risk of OPSCC has been associated with lifetime number of sexual partners, any history of oral sex, earlier age at sexual debut, infrequent use of barrier devices during sex, lifetime history of sexually transmitted disease, and, among men, with a history of same-sex sexual contact (Heck; Gillison 2008).

An association between head and neck cancer and marijuana use has been demonstrated, but it remains uncertain whether marijuana use is an independent risk factor for OPSCC (Gillison 2008). Poor oral health, including periodontal disease and tooth loss, has been implicated in the etiology of oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma, but the associations have been modest and the evidence has generally been inconclusive (Divaris). High dietary intake of fruit and vegetables may be somewhat protective for oral and pharyngeal cancer, though the evidence for this has not been conclusive (Lucenteforte).

Diagnosis & Evaluation

Any patient with a persistent mass of the neck or throat or with symptoms suggesting oropharygneal cancer should be referred to an otolaryngologist (ENT) or head and neck surgeon for further evaluation. Symptoms of oropharyngeal cancer may include throat pain, difficulty swallowing, weight loss, ear ache, voice change, and blood-tinged saliva. Initial evaluation consists of a detailed medical history and comprehensive head and neck examination, generally including examination of the pharynx and larynx with a small flexible endoscope performed in an office setting. Any suspicious tumors of the oropharynx should be biopsied for histopathologic evaluation. In many instances it is possible to perform biopsy in clinic if a lesion is easily accessible either directly through the mouth or via flexible endoscopy. However, in many instances evaluation will require additional examination and biopsy under general anesthesia in an operating room. Such procedures can generally be completed in less than thirty minutes and may be performed on an outpatient basis in most instances. In certain circumstances, it is possible to obtain adequate tissue for diagnosis via a needle biopsy (fine needle aspiration, or FNA) if a lymph node within the neck has become involved with cancer (i.e. a nodal metastasis). Needle biopsy is most often perfomed in clinic and does not require anesthesia, although it may not provide the same degree of staging information as examination under anesthesia. Testing of biopsy specimens for HPV status is recommended in all cases. HPV-positive status predicts better outcomes with standard therapies in general, but this information should not currently be used to tailor decisions regarding treatment with the exception of carefully monitored clinical trials..

All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of OPSCC should undergo evaluation by a multidisciplinary treatment team. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate the primary tumor, involvement of lymph nodes in the neck, and for evidence of metastatic cancer spread beyond the head and neck. Providers may choose to order either computed tomography (CT scan) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck to evaluate the pharynx and lymph nodes in the neck. This scan should be performed with IV contrast in nearly all cases, with the exception of patients with impaired kidney function or an allergy to contrast dye. CT scan of the chest is also indicated in most cases, to evaluate for the presence of metastatic cancer in the lungs or lymph nodes of the chest. Positron emission tomography (PET scan) is also being used with increased frequency for pretreatment evaluation, particularly for patients with advanced-stage disease.

As part of the pretreatment evaluation, all patients who elect to pursue radiation therapy should undergo dental evaluation prior to treatment. As a result of the effects of radiation on bone and surrounding tissue, there is a significantly increased risk of bone-related complications associated with dental procedures which are performed following radiation therapy. In the most severe instances, dental extraction or infection after radiation may result in death of bone tissue (osteoradionecrosis) requiring surgical removal of bone. To minimize the risk of these complications, tooth extractions prior to radiation may be recommended if there is evidence of dental decay or advanced periodontal disease. Pretreatment nutrition and speech and swallowing evaluations should be provided to all patients. Patients experiencing significant weight loss or swallowing difficulty as a result of OPSCC may benefit from surgical placement of a feeding tube into the stomach prior to treatment. However, many patients are able to maintain an oral diet throughout the duration of treatment, and feeding tube placement is not required for all patients. Whenever possible, patients undergoing treatment for OPSCC should continue to eat and drink by mouth during the course of treatment, as long as this is approved as safe by the treatment team. Exercising pharyngeal muscles during treatment can help maintain normal swallowing function both throughout and after cancer therapy.

In a small subset of patients squamous cell cancer is diagnosed only by needle aspiration biopsy of an abnormally enlarged lymph node. In these instances physical exam, imaging and intraoperative biopsies may fail to reveal an obvious cancer in the throat. These cases are referred to as “unknown primary” as the site of primary cancer development remains hidden. In these instances it is particularly recommended that the needle aspirate be tested for HPV. HPV-positive status suggests oropharynx as the most likely site for cancer origin and predicts improved outcomes.

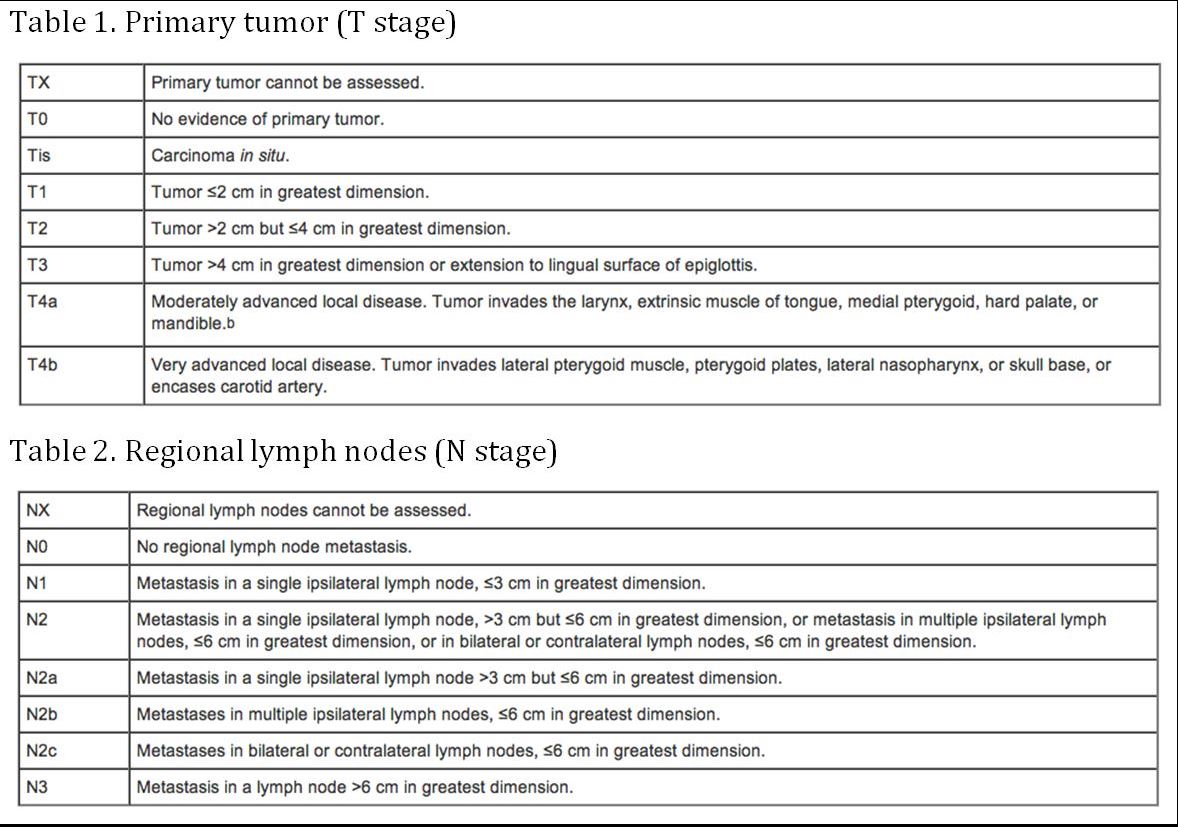

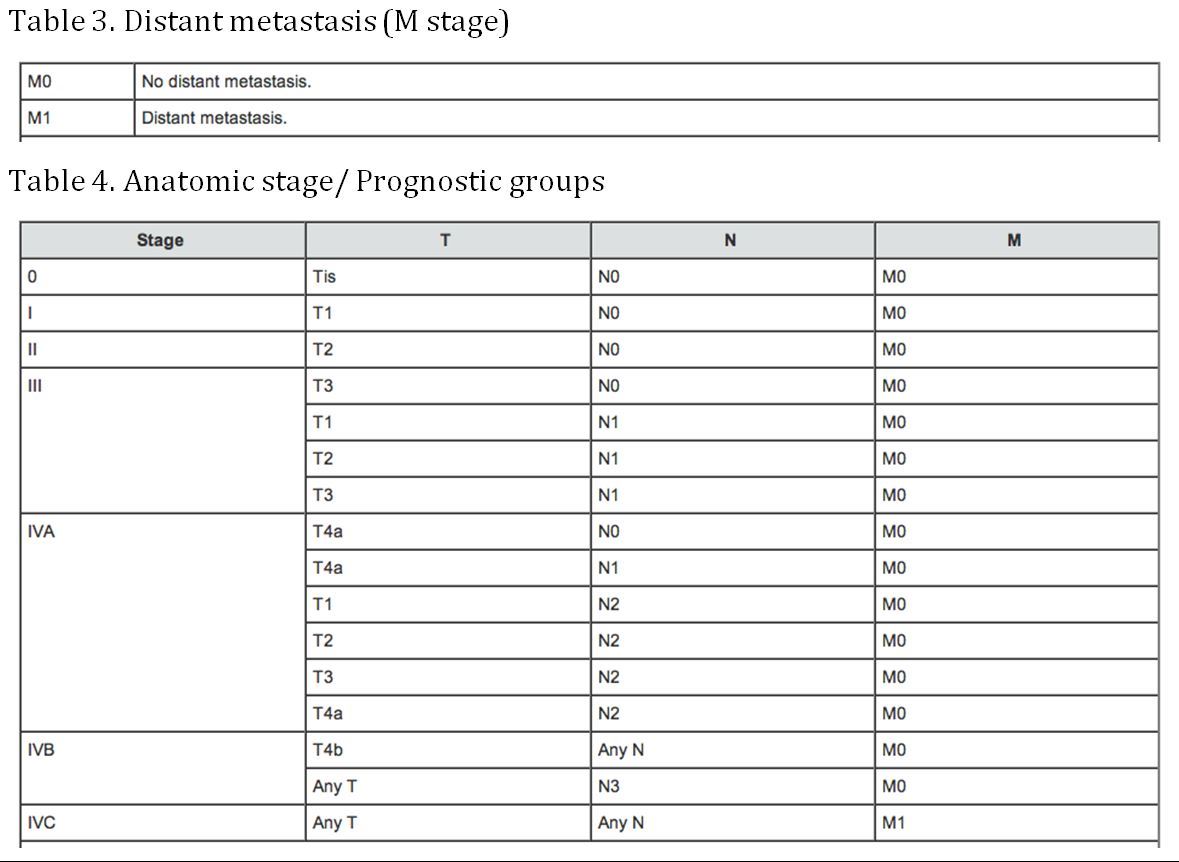

Staging

(AJCC: Pharynx. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2010, pp 41-56)