blog article from the ASN Cutaneous Cancer Section

When large metastases are present in the parotid bed, surgical excision is the preferred modality of treatment. Depending on the extent of the disease, either a classic superficial parotidectomy or a near total parotidectomy with excision of the deep lobe may be required for complete clearance of the nodal tissue. A comprehensive or limited neck dissection may also be concurrently performed.

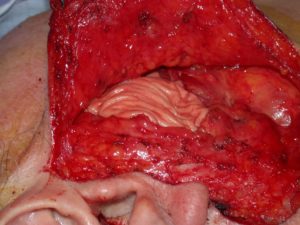

This resection of the parotid gland can lead to significant concavity deformities (Figure 1).

Historically, the volume defect had not been reconstructed. Over time, the soft tissue defect may have less abrupt edges and soften, but the concavity will always be present. The concavity imparts no functional deficits but may result in cosmetic dissatisfaction. In the setting of malignancy, the cosmetic deformity is often considered by most surgeons to be a minor issue in the post-operative period as concern for facial nerve function predominates.

Patients, however, can have differing opinions on the cosmetic outcome of an extensive parotidectomy with concavity deformity1. Ciuman et al demonstrated that parotidectomy for benign disease did not impact overall quality of life, but cosmetic discontent with the facial contour deformity was quite high with 70% reporting a change in appearance.2 Greater than half reported noticeable depression as a result of the cosmetic deformity. Casual observers were also able to notice the contour defect. A review of 274 patients by Bianchi et al discovered that the most essential factor impacting aesthetic outcome was the amount of parotid tissue removal.3 However, the full impact of the contour defect on patient’s quality of life has not been fully elucidated due to the lack of symptom specific questions on quality-of-life instruments1.

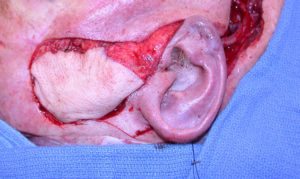

Minimal parotidectomy with neck dissection may yield smaller volume defects and spare involvement of the overlying cutaneous tissue. Surgical reconstruction of the facial skin in this situation is not required and the volume defect may be addressed with a range of reconstructive options. The reconstructive paradigm to address soft tissue defects ranges from sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle flaps, acellular dermal implants, superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) plication, fat graft, and free tissue transfer.4,5 Both the SMAS plication and SCM muscle flap have been shown to be equivalent to soft tissue fillers and result in improved patient satisfaction with their final appearance4. Acellular dermal implants like Alloderm and fat grafting are ideal for smaller volume parotid defects (Figure 2).

Reconstructive options are primarily volume-driven and often imparts no alterations in overall functional status. It is our preference to consider reconstruction in the majority of parotidectomy defects. Small contour defects are easily reconstructed by the ablative team at the time of the initial surgery. Larger defects are approached and a 2-team fashion with involvement of our facial plastics colleagues. When malignancy surveillance is required, it is often done with radiologic imaging so the reconstructive modality used does not impact surveillance or outcome. All reconstructive tissues will atrophy or shrink over time. if adjuvant radiation is expected; fat grafting may atrophy significantly. In our experience it is rare to have patients unhappy with too much bulk in the reconstruction. As with most fat grafting and other parts of the head and neck up to 50% greater volume should be utilized depending on what the next course of treatment is. When there is cutaneous involvement and the defect is not extensive, cervicofacial advancement flaps are ideal for functional and cosmetic reconstruction.

Soft tissue defects greater than 70 cm3 are more common in the setting of advanced metastatic skin cancer to the parotid bed since extensive parotidectomy with concurrent neck dissection is usually necessary, and local constructive modalities are not adequate in these situations.6 There is an increased risk of facial skin involvement with aggressive disease, resulting in another layer of complexity in the reconstruction. Scenarios where local tissue may not be ideal include the large size of the defect, previous rotational flaps disrupting the facial skin or soft tissue blood supply, prior radiation history, heavy smoker, or poor prognostic indicators for wound healing. When defects are of a more significant nature or the wound bed is a more hostile environment, then regional or free tissue transfer should be considered (Figure 3 a,b).5

Utilization of free tissue transfer for parotid skin defects are relatively rare. When necessary, the ideal flap would provide not only coverage of the skin defect, but also would reconstruct the soft tissue defect from parotidectomy and neck dissection. Radial forearm free flaps and anterolateral thigh flaps are most commonly used. The lateral arm flap has recently been proposed in the literature as another alternative option. The ultimate decision depends on the volume of tissue required and patient body habitus (Figure 4a,b,c).4

Patients seem to anecdotally report favorable outcomes after free tissue transfer. Cannady et al described a series of 18 patients with free tissue transfer for soft tissue volume reconstruction of total parotidectomy defects with acceptably cosmetic outcomes reported by patients.5 The benefits of free tissue transfer include healthy vascularized tissue in the wound bed, especially if adjunct radiation therapy is to be pursued post-operatively, adequate skin paddle for facial skin defects with no local tissue available for rotation, and adipose or muscular tissue to address the soft tissue volume loss. Unlike a fat graft, vascularized adipose tissue is less likely to atrophy to the same extent.

In terms of free tissue transfer, radial forearm flap, anterolateral thigh flap, and lateral arm flap are acceptable options when both a skin and soft tissue defect needs to be addressed. When there is no facial skin defect, an adipose fascial free flap from the thigh that results in minimal donor site morbidity may be a more suitable reconstructive modality. Described by Fritz et al, this flap can be harvested as a 2-team approach with a straightforward inset and vascular anastomosis adding an hour or two to the overall length of the surgery.7 Even though vascularized adipose tissue does not shrink like fat grafts, there is a possibility that these grafts will also atrophy to a considerable extent like other free tissue transfers.8 Long-term data is lacking, but there may be a role in overcorrection of the soft tissue volume loss at the time of reconstruction in anticipation of volume loss, especially in the setting of post-operative radiation therapy.

Reconstruction of the parotid bed volume loss may not be like other typical head and neck reconstructions since there is no functional role. Anecdotal evidence from patients report poor cosmetic outcomes and overall dissatisfaction with contour deformities with this defect. There is very little quantitative evidence in the literature regarding its impact on the overall quality of life, but there may still be a role for parotid bed reconstruction to obtain good cosmetic outcomes. Reconstructive options are relatively straightforward and should be considered during pre-operative evaluation. Patient morbidity from reconstruction is relatively minor. The benefits are potentially major.

Mark K Wax MD FACS FRCS(C) 1

Professor Otolaryngology-HNS

Professor Maxillo Facial Surgery

Program Director

Sara Yang MD1

Fellow Microvascular and Reconstructive Surgery

Oregon Health Sciences University

References

- Nitzan D, Kronenberg J, Horowitz Z, Wolf M, Bedrin L, Chaushu G, Talmi YP: Quality of life following parotidectomy for malignant and benign disease. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Oct;114(5):1060-7

- Ciuman RR, Oels W, Jaussi R, Dost P: Outcome, general, and symptom-specific quality of life after various types of parotid resection. Laryngoscope 2012 Jun;122(6):1254-61

- Bianchi B, Ferri A, Ferrari S, Copelli C, Sesenna E: Improving esthetic results in benign parotid surgery: statistical evaluation of facelift approach, sternocleidomastoid flap, and superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap application. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011 Apr;69(4):1235-41

- Militsakh ON, Sanderson JA, Lin D, Wax MK: Rehabilitation of a parotidectomy patient–a systematic approach. Head Neck 2013 Sep;35(9):1349-61

- Cannady SB, Seth R, Fritz MA, Alam DS, Wax MK: Total parotidectomy defect reconstruction using the buried free flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010 Nov;143(5):637-43

- Tamplen M, Knott PD, Fritz MA, Seth R. Controversies in Parotid Defect Reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016 Aug;24(3):235-43. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2016.03.002. Epub 2016 May 24. PMID: 27400838.

- Ciolek PJ, Prendes BL, Fritz MA. Comprehensive approach to reestablishing form and function after radical parotidectomy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018 Sep-Oct;39(5):542-547. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.06.008. Epub 2018 Jun 7. PMID: 29907429.

- Dennis SK, Masheeb Z, Abouyared M. Free flap volume changes: can we predict ideal flap size and future volume loss? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 Oct 1;30(5):375-379. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000832. Epub 2022 Jul 18. PMID: 36036533.